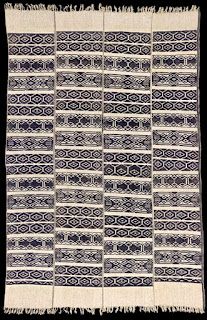

Mapungubwe, Great Zimbabwe and the South East African Textile Tradition

During the mid 13th century, the earliest “complex” stratified culture appeared in southern Africa. In the Limpopo valley of what is now South Africa and Zimbabwe. Agro-pastoral eastern Bantu peoples created a string of settlements starting as early as the 4th century C.E. The increase in east African/Indian ocean trade in the 10th century contributed to a build-up of wealth. This is believed to have driven the development of the Mapungubwe/great Zimbabwe cultural complex. Elaborate dry stone architecture is one of the hallmarks of the various kingdoms associated with this civilization. Early sites are also known for elaborate pottery, and from at least the 10th century, the ancestors of the Mapungubwe peoples were refashioning and exporting imported glass beads. Sites associated with this culture also contain ceramic spindle whorls. This is the earliest evidence of cotton spinning and thus spun textile production in southern Africa, part of understudied, but once-vibrant tradition.

It is suggested that weaving and cotton cultivation/spread into southeastern Africa from the Swahili coast. The single heddled ground loom used across the Zambezi and Limpopo river valley is often cited as having diffused into the region after being adapted from looms used by Bedouin women from the Middle east. However, it should be noted that wild cotton is common across this region. The earliest documented use of the single heddle ground loom is found in ancient Egypt around 5000 YBP, and the domestication of Cotton in Nubia may date back even further. Furthermore, although comparatively rare in Subsaharan Africa, single heddle ground looms are widely distributed across the continent. Although spindle whorls are telltale signs of textile production, they are not always made of stone, pottery, or other non-organic materials. Wooden spindle whorls are commonly used in many regions of Africa, including the Limpopo and Zambezi valleys. Whorls made of this and other biodegradable materials make it difficult to track the exact date of spun yarn production in tropical climates.

Barwe Weaver at loom in Zimbabwe

Comments

Post a Comment