Aso Olona: Production and trade in the Niger Delta

The Aso Olona clothes of the Ijebu Yoruba are one of the most renowned Yoruba women's weaving traditions. These beautiful complex patterned textiles were not only created for use by the Ogboni Elder society ( called Oshugbo in Ijebu) but were important markers of chieftaincy and valued trade items exported to other communities both within and outside of Yorubaland.

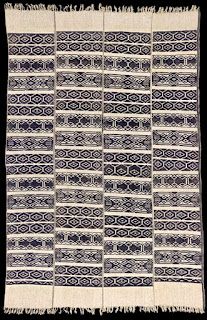

(Above)Indigo and White Aso Olona cloth

Aso Olona (Cloth with patterns, Literally cloth that possesses art) is one of many diverse area-specific textiles made using the upright continuous warp loom. The cloth is most noted as part of the regalia of the Oshugbo elder society. This initiation society is closely associated with the worship of the earth goddess Ile. Through their connection with Ile, who is the arbiter of both life and death, it is Ogboni/Oshugbo that facilitates, orders, and permits the spilling of human blood, in adition to rites and rituals deeply tied to royal authority. The symbolism of Aso Olona is rooted in the iconography of water spirits, stylized depictions of fish, crocodiles, elephants, frogs, sirens, and other aquatic animals. The appearance of these symbols speaks to the deep connection between earth and water In the Yoruba imagination. These elements are ruled by feminine coded spirits, who embody fertility, wealth, abundance while simultaneously holding potentially destructive and deadly powers. A common visual language of potent is shared throughout southern Nigeria and contributed to the popularity of Aso Olona and its related iconography throughout the region.

(Above) Agbareja (Fish Head) pattern

(Above) Opolo (frog) and Gbedu and Gangan (Large single-membrane drum and talking drum)

Although contemporary Aso Olona is mainly woven from imported machine-spun, artificially dyed yarns, the earliest versions of these textiles were made using handspun, naturally dyed cotton. Sunned cotton would be deseeded using an iron bar, then carded into a loose workable mass using a bow. The fiber is then spun into a thread using a drop spindle. These threads are then dyed using a variety of natural dyes. The most common dye used throughout Yorubaland is Indigo derived from the Elu leaf ( Lonchocarpus cyanescens). Indigo threads were commonly used in Aso Olona and continued to be incorporated into the patterning alongside artificially dyed, machine-spun yarns well into the 20th century. The oldest surviving example of these textiles dates from the late 18th century. It possesses Blueish Green (indigo), natural cotton and red yarns of imported silk. Red yarns mported via trans saharan and european trade from a relitively early date. Although the oldest surviving examples of this cloth are around 250 years old,its origins are likely far older. Redish yarns can also be produced using camwood powder (Osun), a red dyestuff made from the heartwood and roots of the Baphia Ntidia tree. The wood or rootstock is painstakingly ground into a paste. Typically this paste is rubbed into the fabric. Still, the ground paste or powder can be boiled in an alkaline solution ( most likely ashes and water) to create a dye solution for cloth and skeins of yarn, creating a more permanent color.

Many of these textiles use a type of shag or Rya type patterning called shaki (tripe). This technique is also commonly used when weaving baby ties. Once the cloth is cut off the loom, the tasseled ends may be left unaltered, braided into bundles, or hemmed. Single sashes measuring between 15 and 22 inches in width and 60 and 72 inches in length called Itagbe are worn as insignia for oshubo elders and other chiefs and priests. Such cloth also appears on Altars to other Orisa in Ijebu and other Yoruba regions. Two paneled iro (wrappers) and three or four-paneled Iborun nla are created by sewing multiple pieces of cloth along the selvage. Women traders would sell these textiles to riverine communities in the niger delta. One of the primary consumers of these cloths was the Ijaw people, who likr the Yoruba and other Nigerian groups worship complex and powerful water spirits . Among the Ijaw, these textiles were called Ikaki (tortoise ) and were one of the most treasured imported African-made textiles used by the Ijaw. In some areas, sumptuary laws made them the exclusive provenance of kings and other types of nobility.

(Above)Kalabari Ijaw Bride in Aso Olona wrapper (Aso olona clothes are also displayed prominantly in the background

This cloth was so popular that Ndoki Igbo weavers far to the east of Ijebu Ode began to incorporate Aso Olona patterns into their own textiles to market them to the Ijaw other groups in the Niger Delta. Aso Olona and numerous other textiles woven by men and women in what is now Nigeria and Benin Republic were also exported to free and enslaved Afro Brazilian communities in Salvador De Bahia. Such cloths were powerful symbols of identity and portable wealth for enslaved and free Africans in Brazil.

Sources:

Aronson, A. (1996). THE MEANING OF YORUBA ASO OLONA IS FAR FROM WATER

TIGHT. In Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings (pp. 1-12). Sacred and

Ceremonial Textiles: Proceedings of the Fifth Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society

of America.

Comments

Post a Comment