Black Marriage Cloth in the Nigerian Woman's Weaving Tradition

The upright loom weaving traditions of southern Nigeria are some of the most important textile traditions of the African continent. The cotton, Raffia, silk, and bast fiver textiles associated with this tradition played crucial roles in the commercial, social, and political histories of west and west-central Africa. The women ( and rarely men) who wove and traded these textiles were at the center of this history. Weaving was a common craft and industry among the Yoruba, Igbo, Edo, Ebira, Igala, Nupe, and Other ethnicities across Nigeria before the turn of the 20th century.

As late as mid 20th century, the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers ( what is now Kogi State) was a region renowned for producing such cloths. The Yoruba, Northern Edo, Akoko, Ebira, and Igala women in the area wove various textiles for domestic use, trade, and as essential parts of puberty, age-grade, and marriage rituals. Numerous village-specific cloths were at the heart of ritual and social life throughout the region. Although these textiles would have particular and sacred functions in the towns and villages where they were created, they were often important trade items that would take on new ceremonial functions amongst the people who imported them, a phenomenon common across the African continent.

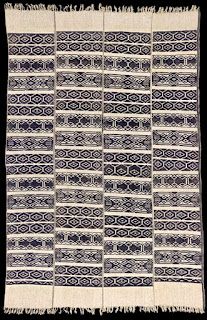

The above image depicts women wearing Adofi Cloth, one of the many handwoven indigo-dyed cotton cloths created by the Bunnu subgroup of the Yoruba people. These cloths are one type in a set of Black marriage cloths women are expected to receive or borrow as part of the complex marriage rituals of the Bunu people. These textiles are made of almost black indigo yarns interspersed with white and red warp stripes. The use of indigo black marriage cloths is also common among other Yoruba groups, most notably of the Igbomina, who are known for their elaborately woven Aso Alara ( cloth of wonders ) textiles, known for their extensive use of complex weft inlays (pictured Below).

Dyeing yarns, this Black color is the work of master dyers, and their dark color is rich with potent symbolism. In Chapter four of “Cloth that does not die, Why Bunu Brides Wear Black,” Elisha P. Renne analyzes the importance of Black marriage cloths among the Bunu subgroup of the Yoruba people, decoding the complicated symbolism of Black cloth in relation to Black skin, femininity, fertility, and the physical world.

“Wives are wrapped with black cloth (aso dudu), portending pregnancy. Like the black rain clouds, women wrapped in black cloth bring - in the form of children - to the community”.

These rich indigo dyed cloths that portend pregnancy are valuable due to their Blackness. The Blue-black of the indigo dye represents fertility. Finished cloth beaten to high sheen mirrors gleaming dark skin. These Black objects, however, can also be dangerous. This creative power can also be destructive, uncontrollable, and polluting. It is a heavy and dense power that caries the ambivalence of life-giving and life-taking hence its symbolic connection of Black cloth with death and burial shrouds. This deep power is exemplified in the use of Black and White cloth as potent protective and curative medicines. Blackness is associated with the rich, feminine, creative potential of the earth itself.

The Bunnu and other Okun Yoruba ( a northeaster cluster of Yoruba languages) have numerous cultural traits that make them unique from other Yoruba groups. Although kings rule each town, their authority does not derive from ideas of divine kinship like other Yoruba groups. Like other Yoruba groups, the Bunu recognize the primacy of the ifa oracle. Still, the worship of the Orisa in the region is antedated by the worship of nature deities known as Ebora. However, it is important to note that varying concepts of Ebora are seen amongst other Yoruba groups. Also, the deeper cosmological and ontological frameworks of Bunu religion are very much in line with the broader Yoruba religious world.

Sources:

Renne, E. P. (1995). Chapter 3 Cloth as Medicine. In Cloth that does not die: The meaning of cloth in Bunu social life. essay, University of Washington Press. (pp. 38-55)

Renne, E. P. (1995). Chapter 4 Why Bunu Brides Wear Black. In Cloth that does not die: The meaning of cloth in Bunu social life. essay, University of Washington Press. (pp. 56-84)

Holmes, J. (1980). Chapter six: The Woman's Vertical Loom. In 1098283381 831836773 V. Lamb & 1098283382 831836773 J. Holmes (Authors), Nigerian weaving (pp. 170-236). H.A. & V.M Lamb.

Comments

Post a Comment